What is sustainability?

Responses to that question depend on who is being asked, and when; the words people use can broadly be categorised under environmental, social, resilience and economic, with significant variation over which of the first 3 is most important.  Organisations often start engaging through resource considerations (energy, water and waste), not least because of the link to operating costs, but that is just the tip of the iceberg. The global agri-food system accounts for around one third of global employment, mostly in precarious smallholder subsistence farming. In developed economies, the numbers directly engaged in agriculture are far lower; the UK’s food supply chain has 4 million jobs, only 10% of which are in agriculture.

Organisations often start engaging through resource considerations (energy, water and waste), not least because of the link to operating costs, but that is just the tip of the iceberg. The global agri-food system accounts for around one third of global employment, mostly in precarious smallholder subsistence farming. In developed economies, the numbers directly engaged in agriculture are far lower; the UK’s food supply chain has 4 million jobs, only 10% of which are in agriculture.

A global system inevitably has a significant environmental as well as social footprint, accounting for around a quarter of all global emissions. Soil erosion, depletion of fresh water resources, food waste and increasingly meat-intensive diets might look like solely environmental challenges, but they also have significant societal consequences. In its annual risk report, the World Economic Forum now characterises ‘water crises’ as a human rather than environmental issue. The current population of around 7.5 billion is projected to be maybe 10 billion by 2050 requiring 60% more food production.

A global system inevitably has a significant environmental as well as social footprint, accounting for around a quarter of all global emissions. Soil erosion, depletion of fresh water resources, food waste and increasingly meat-intensive diets might look like solely environmental challenges, but they also have significant societal consequences. In its annual risk report, the World Economic Forum now characterises ‘water crises’ as a human rather than environmental issue. The current population of around 7.5 billion is projected to be maybe 10 billion by 2050 requiring 60% more food production.

What can business do?

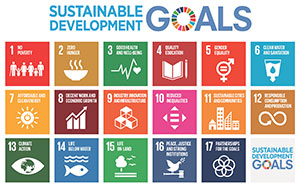

So how should agri-food businesses respond to these complex and inter-connected issues and the expectations of stakeholders around specific challenges like marine plastics and deforestation for palm oil? The most comprehensive guidance is the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), now the go-to framework for environmental, societal and governance (ESG) engagement. As stakeholders look for increased evidence of responsible conduct, working to the SDG framework represents a great opportunity to focus action. Comprising 17 inter-linking sets of targets, the Goals encompass many of the issues reflected in recent and probable future regulation.

But the SDGs are not just about food and agriculture. They have a very broad scope, covering all aspects of human endeavour, and organisations seeking to align with the SDG agenda can find them overwhelming. This is not least because at detail level they’re written more for government than for business and making them relevant to the day-to-day is not always straightforward. Even at the top-line Goal level there is a risk of relating them to business activities in a way which can mis-attribute an organisation’s real impacts.

But the SDGs are not just about food and agriculture. They have a very broad scope, covering all aspects of human endeavour, and organisations seeking to align with the SDG agenda can find them overwhelming. This is not least because at detail level they’re written more for government than for business and making them relevant to the day-to-day is not always straightforward. Even at the top-line Goal level there is a risk of relating them to business activities in a way which can mis-attribute an organisation’s real impacts.

Finding a way

Finding a way

Getting to grips with the spirit of the SDGs needn’t be daunting. Specialist organisations, including mine, help businesses find their way through the maze of ESG issues they face. A structured process drawing on the experience of the team within the business and the expertise of an external facilitator gets to the genuinely material issues. It also helps avoid the risk of ‘greenwash’ and the associated reputational damage it can cause. Progressively more businesses in the UK and elsewhere are building their ESG reporting around the Goals, and awareness among younger people is growing as they now feature prominently in UK Business Schools.

Anyone who followed December’s COP24 meeting in Poland will know the scale of the problem. A year earlier, Blue Planet II triggered citizens, governments and businesses across the world to take action on single-use plastics. Indeed, ‘single-use’ became Collins Dictionary’s word of 2018. Along with their words to define ‘sustainability’, I also often ask people where responsibility for a sustainable society lies. Citizens, particularly younger citizens, expect business to do the due diligence on their behalf. That in itself is a pretty compelling reason to engage with the SDG agenda.

Dr Gavin Milligan is director of Green Knight Sustainability Consulting

www.greenknight.consulting